If you've Googled "AI Software Engineer" lately, you probably got two very different results.

In one corner, there's a high-paying human role focused on building AI systems. In the other, there's a robot—like Devin, Replit Agent, or Manus—promising to do that job for free.

It creates a bit of an awkward standoff. Are these tools coming for your job, or are they just really eager idiots?

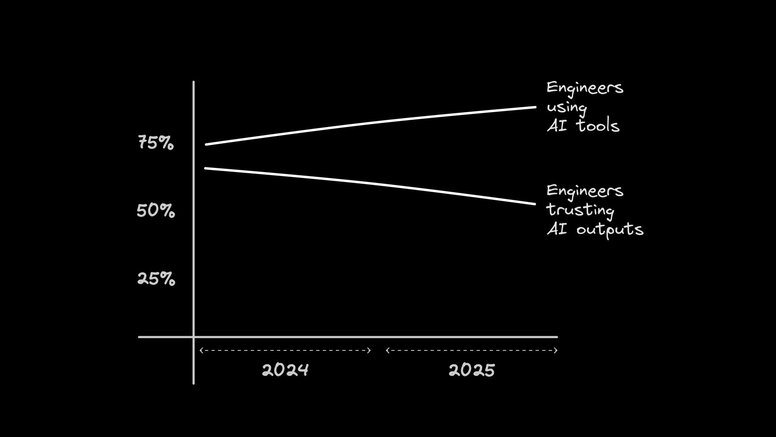

Here's the paradox: 84% of developers now use or plan to use AI coding tools, up from 76% last year. The market is projected to hit $25 billion by 2030. Cursor crossed $1 billion in annualized revenue. Claude Code went from zero to $400 million in five months.

And yet, trust is declining. Nearly half of developers actively distrust AI-generated outputs, which is up from 31% in 2024. Only 3% say they "highly trust" the code.

The culprit? 45% of developers report frustration with AI that's almost right—code that looks correct, then blows up in production.

If it all sounds familiar, that's because this is exactly how you'd describe an eager intern. Fast, enthusiastic, 80% of the way there. But that last 20% still requires your supervision.

The industry loves to swing between "AI will replace us all" and "AI is just a fancy autocomplete." But the data suggests something more nuanced: these tools are powerful, widely adopted, and genuinely useful when managed correctly.

That managed correctly part is the key. The “AI software engineer” of the future isn't just a coder, and they aren't just a prompt writer. They're an Orchestrator managing a team of specialized agents.

They’re still accountable for code delivery, but they spend less time typing code manually and more time controlling agents, reviewing AI output, and integrating changes into real systems.

AI tools write most of the code; the engineer ensures it’s the right code, safely shipped.

And for the record: this isn't a demotion. It's an abstraction layer up. But like any promotion, it comes with some growing pains and a whole new toolkit.

So, what does this look like in practice? Well, you run the AI software development loop: spec → onboard → direct → verify → integrate.

Think of it less as “management” and more as technical direction. Senior engineers already spend less time typing and more time shaping systems. Agents just push that trend to the extreme.

Your job isn’t to write the loop itself; it’s to make sure the loop solves the user’s problem and doesn’t explode in production.

Here’s the day-to-day:

This is where you decide what matters next and turn it into something an agent can reliably execute.

Spec’ing looks like:

- Picking the highest-leverage thing to build/fix next (impact > effort)

- Breaking the work into a small, verifiable slice (one PR-sized unit)

- Writing acceptance criteria (inputs/outputs, edge cases, UX constraints)

- Calling out risks up front (perf hotspots, security boundaries, migration concerns)

A good spec turns “almost right” code into shippable code, because you’ve made “done” super clear.

Agents are only as smart as the context you give them. You wouldn’t throw a new intern into a codebase without a walkthrough—don’t do it to your agent.

Onboarding looks like:

- Pointing it at your repo conventions (

CONTRIBUTING.md, lint rules, test commands) - Showing it your component system (e.g.

shadcn/ui), design tokens, and patterns - Defining constraints (what not to touch, what must stay backward compatible)

The payoff is fewer hallucinations and fewer “looks right, fails later” PRs.

And don’t worry, just like training an employee, onboarding is something that gets easier over time, because you have existing rules and systems you can point the agent to.

If your spec defines the target, direction is the handoff: you package the task so a specific agent can run with it without guesswork.

Direction looks like:

- Assigning the right agent/tool for the job (visual editor vs IDE vs autonomous refactor)

- Pointing at the relevant files/components and what to reuse

- Stating constraints as explicit guardrails (“don’t change API shape,” “keep this behavior,” “no new deps”)

- Defining the deliverable (“open a PR,” “include tests,” “add screenshots,” “note tradeoffs in the description”)

And remember, micromanaging agents is a trap. Today’s coding agents can do far more than you may realize. Treat them more like a coworker.

Instead of “add a useState here,” you give intent and boundaries, like, “This component needs to track selected items, persist them to the URL, stay accessible, and keep the existing keyboard behavior.”

It’s more than just “prompt writing.”

Trust is the bottleneck, so this becomes the highest-leverage part of the job.

You review agent output like you’d review a junior engineer’s PR, but with extra paranoia:

- Correctness (edge cases, race conditions, error handling)

- Performance (N+1 queries, unnecessary re-renders, overfetching)

- Security (auth boundaries, injection, secrets, SSRF)

- Tests (new coverage for the changed behavior, not just snapshots)

AI can ship broken code faster than humans can. Your job is to stop bad code from becoming “working” code in prod.

We’ve also got some tips on not burning out on AI code review.

You’re the glue between tools and systems:

- Decide when a visual/scaffolding tool is enough vs when you need an IDE deep dive

- Break big work into tasks agents can complete reliably

- Merge conflicts, verify CI, stage rollouts, and monitor regressions

Agents don’t know when they’re the wrong tool for the job. You do.

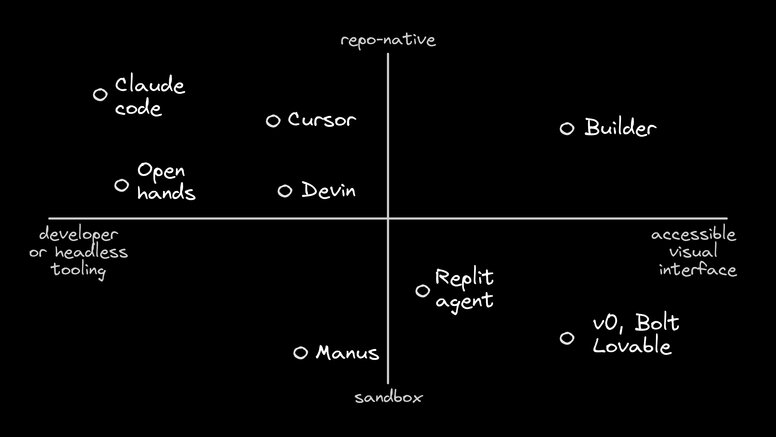

Once you think in this loop, tools stop being “AI coding apps” and start being specialists you plug into different steps.

It's not just Cursor or Devin or v0 anymore. In practice, the market has split into scaffolders, autonomous refactor agents, repo-native visual tools, and agentic IDEs.

Kinda like the world’s most boring DnD group.

Tools like Replit Agent or Lovable are your “0 to 1" sprinters. They handle the messy setup—database (Supabase), auth, and deployment—before you’ve even finished your coffee.

Their superpower is speed to "Hello World." If you need a prototype by lunch, these are your best friends. They often handle hosting and (very basic) backend integration, so you look like a wizard.

The big catch with these tools are that they operate in a sandbox. Everything works great until you have to export to your real repo. Once you leave their ecosystem, the magic features break, and you’re left maintaining code you didn't write.

They’re brilliant for 0 to 1, but brittle for 1 to 100.

Then you have Devin (by Cognition) and OpenHands (formerly All Hands AI). These are designed for the gnarly stuff in existing repos. Need to update an API call across 50 files? Don't want to ruin your afternoon? Send Devin.

Devin has high autonomy. It plans multi-step tasks, uses a shell, and even browses the web to read docs. OpenHands in the open-source, model-agnostic version of Devin, but it requires some setup to get working.

The problem with these tools is they’re headless. They’re incredible at logic and backend refactors, but they struggle with "feel." Ask them to "fix the layout shift" or "make the animation snappier," and you have to translate visual intent into text paragraphs.

They're also async only: you assign a task and wait. You can't iterate with the AI in real-time, if needed.

Builder sits in the middle to solve both problems. It’s not a sandbox and it’s not headless.

It’s a visual IDE that lives inside your existing codebase.

- Solves the "Sandbox Trap": It works with your existing components and Git branch from minute one. No export tax.

- Solves the "Headless" problem: It’s a true visual editor running in a real browser environment. This means non-devs (PMs, Designers) can verify changes visually without pulling code, and the AI validates its work against the actual rendered DOM, not just the code.

- Solves the "Async" gap: You can work interactively for fast cycles, OR tag

@Builder.ioin Slack, Jira, or GitHub issues and PRs to handle long-running refactors just like Devin would.

For a lot of work done in Builder, you may never need to touch an IDE at all. But for a decent chunk—complex debugging, performance tuning, writing intricate tests—you still will. That's where agentic IDEs like Cursor and Claude Code come in.

These are where you go when you really need to get your hands on the code itself. They sit inside your codebase, understand your project structure, and give you the control to make surgical fixes that agents can't quite nail.

Now that you’ve seen the categories, the strategy gets simpler: pick one tool to go from 0→1 and one tool to go from 1→100. Then get really good at the handoffs.

Let’s say we’re building a new analytics dashboard in your Next.js app. Here’s how it plays out with Builder and Cursor.

We start with Builder because it’s "multiplayer." A PM or designer can spin up a dedicated instance on a fresh branch and start building immediately. The developer doesn't even have to be involved yet.

- Scaffold: "Create a dashboard layout at `/analytics." (Done.)

- UI: "Import this 'Analytics View' from Figma." Builder uses your components to build it, so it doesn't look like a generic Bootstrap template.

- Basic Logic: "Add a filter for the date range."

Why start here? Because it creates a real PR that anyone can run. Developers can jump in to quickly prototype ideas without blowing up their local environment, but they don't have to. Your PM can get the ball rolling without you writing a single div.

For reference, visual editing in Builder looks like this:

Now things get real. We need data.

You can actually stay in Builder for this. Thanks to MCP Servers, you can connect your database (like Supabase or Neon) directly. You could say something like, "Fetch the analytics data from Supabase and wire it up to this chart." (And we've got some live examples of the Supabase workflow in action.)

For heavy algorithmic logic or complex performance tuning, you might still tab over to Cursor (or your AI IDE of choice).

- "Hey, this chart rendering is slow. Optimize it for large datasets."

- "Write some tests for this transformation logic."

- Or, worst case scenario, time to get your hands dirty with code.

The handoff is smooth because Builder integrates deeply with your repo—whether you're visually editing or coding, it's all the same codebase.

Later, you realize you need to update a deprecated API field across 50 components. Do not do this manually.

If you're using Builder, just stay there. Assign a Jira ticket to the Builder bot or tag @builder-bot on a PR: "Update all instances of user.id to user.uuid." Because it indexes your entire codebase, it handles the refactor just like a dedicated agent.

Tagging Builder in Jira generally looks like this:

If you aren't on Builder, this is where you tag in Devin or OpenHands. "Go find every instance of user.id and swap it to user.uuid."

Then, watch a YouTube video about the next overhyped AI model.

So, why do AI Software Engineers get paid the big bucks? It’s about leverage.

If you love typing syntax, this transition might feel uncomfortable. But the engineers who resist it are going to find themselves competing with agents who don't sleep. The engineers who embrace it? They’re going to be managing a team of ten agents and shipping product faster than they ever thought possible.

Your resume is going to change. It’ll say less about "wrote 10,000 lines of React" and more about "Architected systems using Agentic Orchestration." (And no, that's not just a euphemism for vibe coding.)

The "10x Engineer" used to be a myth about a lone genius. In 2026, it’s just an engineer who learned to manage ten agents.

Builder.io visually edits code, uses your design system, and sends pull requests.

Builder.io visually edits code, uses your design system, and sends pull requests.

Connect a Repo

Connect a Repo