Async / await was a breath of fresh air for those who did web development prior to 2014. It simplified the way you write asynchronous code in JavaScript immensely.

However, as with everything in the JS world and programming, it does have a few gotchas that can be a problem later.

But before we get down to business and give you those sweet tips you crave to avoid shooting yourself in the foot, I thought it’d be nice to first take a little trip down memory lane.

Depending on how long you have been in web development, you may have seen the evolution of handling async operations in JavaScript.

Once upon a time, before the days of arrow functions and Promises, prior to ECMAScript 6 (2015), JS devs had only callback functions to deal with asynchronous code.

So, writing code “the old way” would look like the example below.

function getData(callback) {

setTimeout(function() {

const data = { name: 'John', age: 30 };

callback(data);

}, 1000);

}

function processData(data, callback) {

setTimeout(function() {

const processedData = Object.assign({}, data, { city: 'New York' });

callback(processedData);

}, 1000);

}

function displayData(data) {

setTimeout(function() {

console.log(data);

}, 1000);

}

getData(function(data) {

processData(data, function(processedData) {

displayData(processedData);

});

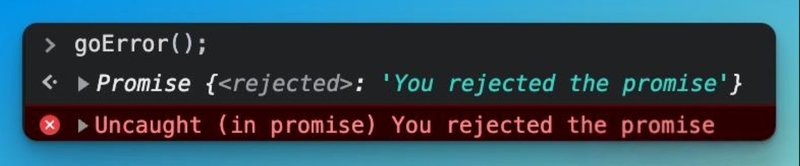

}); From a glance, this might seem somewhat manageable, but this lead to “beautiful” code like the below that you need Ryu from Street Fighter to indent (props to reibitto for creating Hadoukenify).

That is what you call “callback hell”.

To escape this, ES6 hit the scene with the mighty Promise web API.

The idea is that an async task has a lifecycle consisting of 3 states: pending, fulfilled (also called resolved), or rejected.

Furthermore, this came with a novel concept - then() which allowed us to do something with a resolved promise value.

But not only.

This also allowed returning a promise as the resolved value which in turn can also have a then() method, which ultimately enabled promise chaining.

The gist is that you can pipe a returned value from one async operation to the next.

A great step forward with great power for sure!

However, as good ol’ Uncle Ben told Peter Parker “with great power…” - I’m assuming you know the rest of the phrase 😉.

So, please don’t do this:

Promises are great, but as we’ve learned from the above, they can be poorly written.

What more is that even though JavaScript is async by nature, a lot of its APIs are synchronous and are much easier to reason about.

Reading top to bottom is more natural to us as humans, and even more so, reading code the same way helps maintain the order of execution of a program more clear.

So now, if we take the code from the pre-ES6 era, we can refactor it using both Promises and async / await:

const getData = () => new Promise((res, rej) => res({ name: "John", age: 30 }))

const processData = (data) => new Promise((res, rej) => res({ ...data, city: "New York" }))

const runProgram = async () => {

const data = await getData();

const processedData = await processData(data);

console.log(processedData);

};

runProgram()The thing to note here is that we need to have an async function in order to use the await keyword.

Overall, it’s just much more readable. We wait for our data in one line, then we wait to process it, and finally, we log it.

Clean, and without all that nesting and indentation.

But as I’ve mentioned, it can sometimes lead to unexpected footguns.

Let’s dive in.

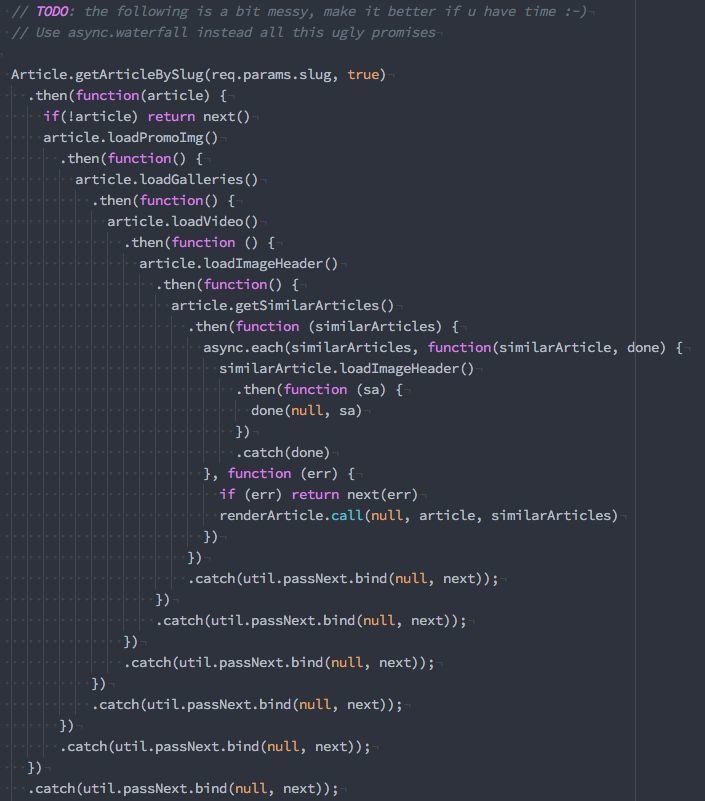

One of the most common footguns when using async/await is not handling errors correctly. When using await, if the awaited promise rejects, an error will be thrown.

As mentioned, the Promise instance has a reject method, which might help handle that situation.

You might think that if write your promise like the snippet below, that should do it.

// shouldReject will help us simulate an error

function doAsyncOperation(shouldReject = false) {

return new Promise(function (resolve, reject) {

// reject when the condition is true

if (shouldReject) {

reject('You rejected the promise');

}

const timeToDoOperation = 500;

// wait 0.5 second to simulate an async operation

setTimeout(function () {

// when you are ready, you can resolve this promise

resolve(`Your async operation is done`);

}, timeToDoOperation);

// if something went wrong, the promise is rejected

});Then you’d use it like so:

async function go() {

const res = await doAsyncOperation();

console.log('this is our result:', res);

// will log: "this is our result: Your async operation is done"

}However, if we simulate an error and run about the same code, for example:

async function goError() {

const res = await doAsyncOperation(true);

console.log('this is our result:', res);

console.log('some more stuff');

}Nothing will be logged to the console, besides our rejected promise:

Our logs were swallowed by the promise rejection 😱.

A common way to handle this would be to wrap our await statements in a try...catch block.

async function goTryCatchError() {

try {

const res = await doAsyncOperation(true);

console.log('this is our result:', res);

} catch (error) {

console.log('oh no!');

console.error(error);

}

}But guess what? There’s a footgun here.

Let’s observe how this approach can fail.

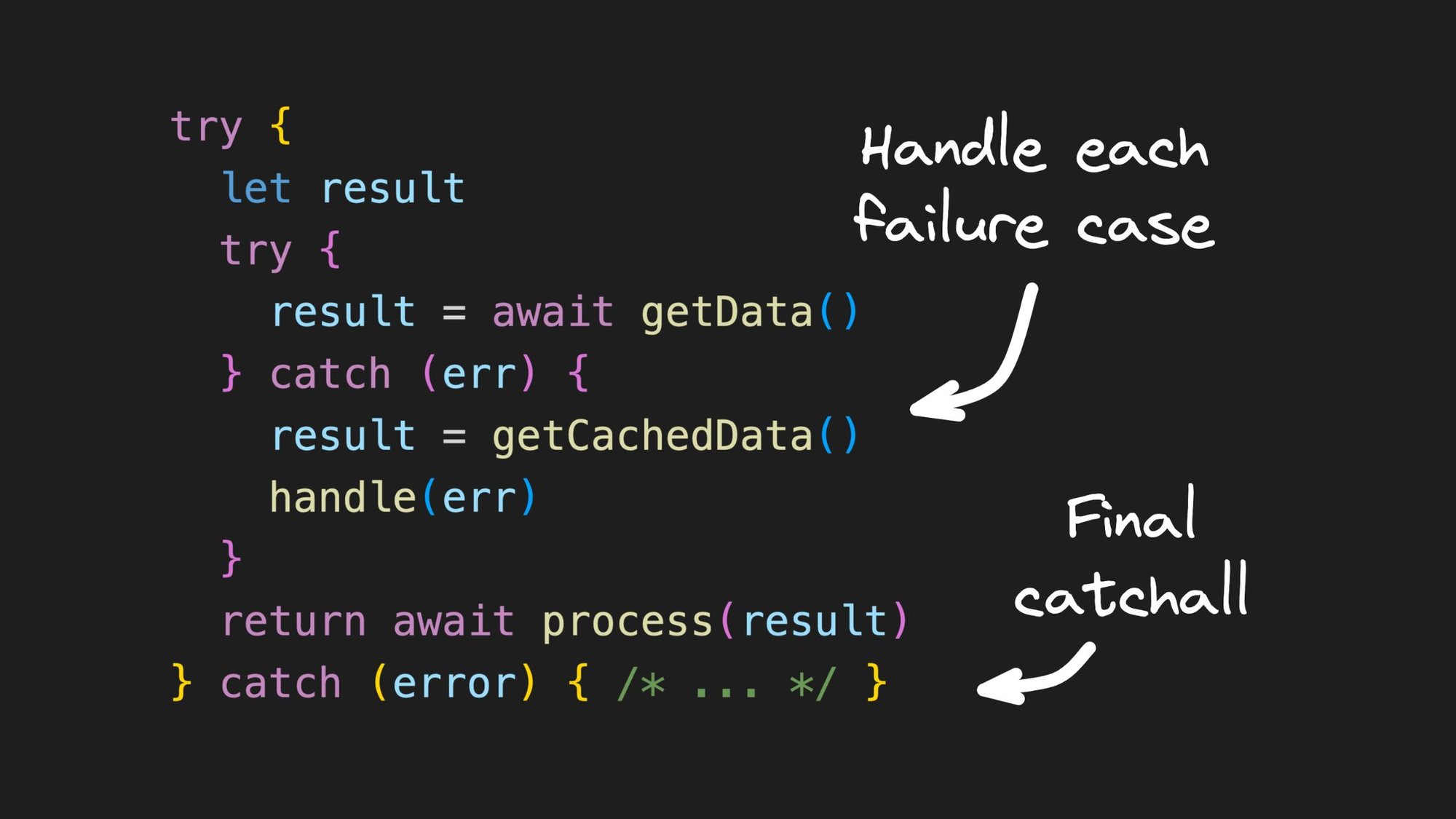

In case you have a flow that has multiple awaits think about creating alternative sub-flows. As David Khourshid wrote a while back ago: “Async/await is too convenient sometimes”:

Let’s use his contrived example to illustrate this:

// This has no error handling:

async function makeCoffee() {

// What if this fails?

const beans = await grindBeans();

// What if this fails?

const water = await boilWater();

// What if this fails?

const coffee = await makePourOver(beans, water);

return coffee; // --> this flow can fail at any step

}Now with error handling and multiple try...catch blocks:

async function makeCoffee() {

try {

let beans;

try {

beans = await grindBeans();

} catch (error) {

beans = usePreGroundBeans(); // <-- alternative sub-flow

}

const water = await boilWater();

const coffee = await makePourOver(beans, water);

return coffee;

} catch (error) { // <-- general error handling

// Maybe drink tea instead?

}

}The point is that you should have try...catch blocks at the appropriate boundaries for your use cases.

Some like to just write:

const beans = await grindBeans().catch(err => {

return usePreGroundBeans();

});

// ...It's a good way to go as well. Allows using const instead of let and read the code flow a bit nicer.

There are also libraries out there that can assist with handling errors as well.

I recently learned about fAwait, which approaches in a more functional way of writing. It adds some utility functions and a way to pipe errors into the next "layer" and add side effects. Kind of like middlewares.

Instead of code like this:

const getArticleEndpoint = (req, res) => {

let article;

try {

article = await getArticle(slug);

} catch (error) {

// We remember to check the error

if (error instanceof QueryResultError) {

return res.sendStatus(404);

}

// and to re-throw the error if not our type

throw error;

}

article.incrementReadCount();

res.send(article.serializeForAPI());

};You can write it like this:

const getArticleEndpoint = async (req, res) => {

// This code is short and readable, and is specific with errors it's catching

const [article, queryResultError] = await fa(getArticle(slug), QueryResultError);

if (queryResultsError) {

return res.sendStatus(404);

}

await article.incrementReadCount();

const json = article.serializeForAPI();

res.status(200).json(json);

};I haven't tried it yet, but it looks interesting.

Another footgun is having too many sequential awaits, similar to the previous example.

The caveat is that the await keyword, as I’ve mentioned, makes async code execute in a synchronous fashion. That is, as implied from the keyword, each line waits for a promise to be resolved or rejected before moving to the next line.

There’s a way to make promises execute concurrently, which is by using either Promise.all() or Promise.allSetteled():

// Good, but doesn't handle errors at all, rejected promises will crash your app.

async function getPageData() {

const [user, product] = await Promise.all([

fetchUser(), fetchProduct()

])

}

// Better, but still needs to handle errors...

async function getPageData() {

const [userResult, productResult] = await Promise.allSettled([

fetchUser(), fetchProduct()

])

}For a deeper dive into this topic, read Steve’s post.

In conclusion, async / await is a powerful tool for simplifying asynchronous code in JavaScript, but it does come with some footguns. To avoid common pitfalls, it's important to handle errors correctly, not overuse async/await, and understand execution order. By following these tips, you'll be able to write more reliable asynchronous code that won't break later.

About me

Hi! I’m Yoav, I do DevRel and Developer Experience at Builder.io.

We make a way to drag + drop with your components to create pages and other CMS content on your site or app, visually.

You can read more about how this can improve your workflow here.

You may find it interesting and useful!

Builder.io visually edits code, uses your design system, and sends pull requests.

Builder.io visually edits code, uses your design system, and sends pull requests.

Connect a Repo

Connect a Repo